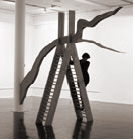

Tristan remembered the day - a blistering hot day, with an electric atmosphere - when he had attempted to draw Isolde. He had wanted to catch her as she was forever. Tristan remembered the day - a blistering hot day, with an electric atmosphere - when he had attempted to draw Isolde. He had wanted to catch her as she was forever.

But she would not stop moving: a gnat got in her eye, another was tickling her chin; any excuse was good enough. If only she could have kept still, even for a second. But it was hopeless. When night fell, they decided to head home without his having been able to even begin a sketch. On the way home, they didn't speak a word; the tension was extreme. The wind had come up, dark clouds gathered before them. The village was still far away. They didn't know any better than to climb up to that branch to take shelter. The night was black. Tristan could feel that Isolde was frozen with fear. She had stopped moving. He took out his sketch pad and waited for the first lightning bolt to illuminate her stillness. The bolt fell very close to her. He saw her marvelously petrified; his hand moved across the paper at lightning speed; he didn't have the impression that he was guiding it, it was as if the lightning was taking care of that. A second lightning bolt enabled him to discover what he had drawn. A skull. He had drawn a skull. Most likely Isolde's skull.

The rain began to fall. Big drops burst on the drawing paper. Blackening upon contact with the charcoal, they overturned his drawing. A drop fell in the eye socket, another brushed the jawbone. As each second passed, the skull took on a different expression. With both hands, Tristan flicked the drops away as if they were no more than vulgar gnats. But it was without hope. Isolde's image would never be captured.

|

Tristan remembered that autumn day when he and Isolde had been joined one to the other. He had wanted to draw her wearing the dress with fine purple motifs. She was posing in a circle of heather which gave the impression that there had once been a pond there. He had climbed up to the branch to get a better perspective on the scene and had placed a Bristol board before him whose dimensions were as large as his ambition. What Tristan wanted was for his drawing to give the impression of a total fusion between human figure and landscape. At first glance, it would be impossible to tell what was part of her and what was part of the surrounding vegetation. A bit like when, from Calais, one looks out over towards England and cannot really tell if the dark line one sees resting on the horizon is a cloud among clouds or if it is really England; or if this cloud a bit heavier than the others already allows us to stroll through the streets of London or if it holds us back in the mist that covers the cliffs of Dover. Tristan remembered that autumn day when he and Isolde had been joined one to the other. He had wanted to draw her wearing the dress with fine purple motifs. She was posing in a circle of heather which gave the impression that there had once been a pond there. He had climbed up to the branch to get a better perspective on the scene and had placed a Bristol board before him whose dimensions were as large as his ambition. What Tristan wanted was for his drawing to give the impression of a total fusion between human figure and landscape. At first glance, it would be impossible to tell what was part of her and what was part of the surrounding vegetation. A bit like when, from Calais, one looks out over towards England and cannot really tell if the dark line one sees resting on the horizon is a cloud among clouds or if it is really England; or if this cloud a bit heavier than the others already allows us to stroll through the streets of London or if it holds us back in the mist that covers the cliffs of Dover.

Tristan spent the whole day on his drawing, but managed to attain his goal. When he raised his head to thank his model for her patience, he saw that she was up to her neck in swamp mud. She must have been sinking into it since morning, while he, completely absorbed in his drawing, had neither seen her sink, nor heard her cries. He had drawn her from memory only.

Isolde's arms were flailing desperately in search of something to keep her on the surface. Without thinking, Tristan threw her the Bristol whose large dimensions would allow her to grab hold. He saw her pull herself up out of the mire and heave herself onto the Bristol with mud dripping off her feet. For a moment, he hoped to be able to recover the drawing to frame and hang in their bedroom. But he saw it disappear hopelessly into the quick soil, a bit like when, from Calais, we see the boats disappearing into the dark cloud that we had wanted to believe was the coast of England. And we are so disappointed by the fragility of our illusions that we hope to see the cloud speed towards us and swallow us up.

|

A few months earlier, Tristan had been assailed by doubt: What if someone else had come between them, and Isolde did not dare tell him? More and more regularly, she was the one who asked him to draw her in the forest. She posed for hours. She was doubtlessly taking advantage of these sessions to get away from him. He did not notice a thing, even though his concentration was extreme. But perhaps he was like those insomniacs who think they haven't slept a wink when in fact their waking state has been broken by a sleep of which they were not conscious. A few months earlier, Tristan had been assailed by doubt: What if someone else had come between them, and Isolde did not dare tell him? More and more regularly, she was the one who asked him to draw her in the forest. She posed for hours. She was doubtlessly taking advantage of these sessions to get away from him. He did not notice a thing, even though his concentration was extreme. But perhaps he was like those insomniacs who think they haven't slept a wink when in fact their waking state has been broken by a sleep of which they were not conscious.

In order to prevent Isolde's misconduct, Tristan made her balance high on the branch and as she posed, he decided to pay attention only to any suspicious moves she might make. But she didn't move at all. In the position in which he had placed her, it was inconceivable that she could hold the pose for so long unless there were an exterior force - someone, for example - holding her up from behind.

Though he could not see him, Tristan decided to concentrate solely on the presence of this someone. He watched so intently and for so long that he began to feel dizzy and almost fainted. But he came back to himself in an instant, as if a mysterious hand had caught him up by the skin of his back.

At last the truth was revealed to him. If someone else were there, he was not hiding behind her but behind him. The reason Isolde managed to balance high on the branch with her chest thrown out was to better seduce the one that, standing behind Tristan, held him like a marionette animated by doubt.

|

Tristan recalled that winter day when, after three months of separation, he had seen Isolde again in the forest. To seal their reconciliation, he wanted to draw her at the foot of the tree where they had once taken shelter. He was trembling with cold, but the desire to find her again was stronger than all the rest. Just when he was about to begin drawing, he sneezed so violently that a drift of snow on the branch above her fell and covered her completely. Isolde disappeared into the white of the forest. He felt completely alone. In one blow, the pain of their separation was reawakened. He could not take his eyes off the black branch that, freed from its snow, rose before him like a sign of fate. If he could have cut it off, it would have made a perfectly good walking stick to accompany and support him in his new solitude. Tristan recalled that winter day when, after three months of separation, he had seen Isolde again in the forest. To seal their reconciliation, he wanted to draw her at the foot of the tree where they had once taken shelter. He was trembling with cold, but the desire to find her again was stronger than all the rest. Just when he was about to begin drawing, he sneezed so violently that a drift of snow on the branch above her fell and covered her completely. Isolde disappeared into the white of the forest. He felt completely alone. In one blow, the pain of their separation was reawakened. He could not take his eyes off the black branch that, freed from its snow, rose before him like a sign of fate. If he could have cut it off, it would have made a perfectly good walking stick to accompany and support him in his new solitude.

Despite the cold, Tristan managed to pick up the pencil and draw the branch in all of its detail. Drawing the branch enabled him to begin to get used to his sweet solitude. He even felt stronger than ever. He began to dig through the snow where poor Isolde had been buried for several minutes to take her with him back to the village. Isolde was frozen with cold. Tristan carried her for five steps and then, exhausted, leaned up against her. He was careful not to hug her too closely in order to avoid that a new found bodily heat would restore the flexibility that would make him lose the memory of his dear stick.

|

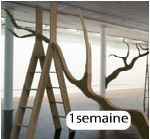

Tristan recalled the state of terror he had been in a week before their marriage. He had watched the day arrive with dread, thinking that the ceremony and its procession of conventions would ruin their relationship. To rid himself of this fear, he decided to draw Isolde as Eve proudly reaching for the apple. Together, they canvassed the forest to find a wild apple tree to use in the composition. It was already late in the season, they found only one apple tree with a single apple hanging from a high branch. Tristan recalled the state of terror he had been in a week before their marriage. He had watched the day arrive with dread, thinking that the ceremony and its procession of conventions would ruin their relationship. To rid himself of this fear, he decided to draw Isolde as Eve proudly reaching for the apple. Together, they canvassed the forest to find a wild apple tree to use in the composition. It was already late in the season, they found only one apple tree with a single apple hanging from a high branch.

But Tristan did not abandon his project. He undressed Isolde as Eve and placed her up on his shoulders so that she was on the same level as the apple. This operation naturally complicated the drawing process as he had absolutely no distance with his model. Happily, the sun came out and cast a detailed shadow of his Eve on the ground before them.

Tristan barely had the time to sketch in a line when the sun disappeared again. For hours on end, with his Eve on his shoulders, he turned round the apple like the moon turning round the earth, hoping that he was thus following the course of the sun and would be able to take advantage of its reappearance from behind the clouds. But the sun's appearances were so furtive that he never had the time to draw more than one or two lines.

After a few hours, the wind finally came up and swept the clouds away but, unfortunately, a gust stronger than the others shook the apple and made it come off the tree. Tristan saw it splotch all over his drawing pad. All around the squashed apple, his miserable little charcoal lines squirmed like a bunch of repulsive worms that were going to attack the fruit. He was awe-struck by the realism of his drawing. His wedding had suddenly taken shape and substance. His Eve seemed so heavy that he no longer had the strength to bear her. She got dressed again and they headed home without saying a word to each other. He spent the rest of the week looking at his drawing and eating his heart out from inside.

|

|